List of Figure Captions

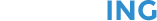

Figure 1. Portrait of Rutherford in Kapitsa’s Office with Rutherford’s quote to remind Pyotr Kapitsa of the direction set up by Rutherford. (From the Archives of the Kapitza Memorial Museum)

On 15 May 1936 Rutherford wrote to Kapitsa:

“This term I have been busier than I have ever been, but as you know my temper has improved during recent years, and I am not aware that anyone has suffered from it for the last few weeks!

… Get down to some research even though it may not be of an epoch-making kind as soon as you can and you will feel happier. The harder the work the less time you will have for other troubles. As you know, ‘a reasonable number of fleas is good for a dog’ – but I expect you feel you have more than the average number!..”

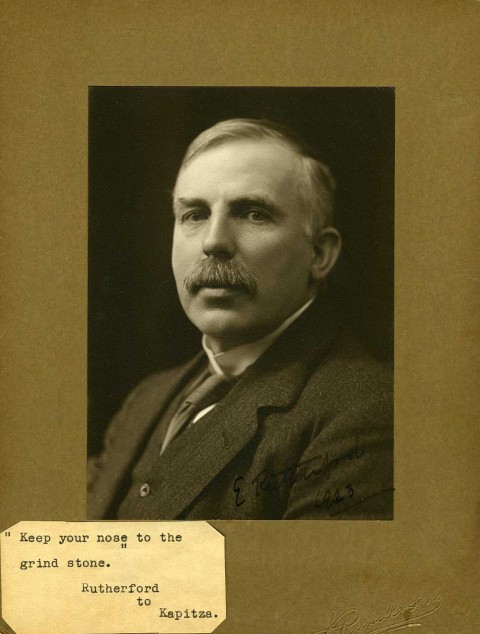

Figure 2. Selected literature on the topic of “Lord Rutherford and Russia”

For more references please go to: https://www.olgasuvorova.com/product/read-rutherford-and-russian-physics-the-critical-influence-of-the-human-factor/

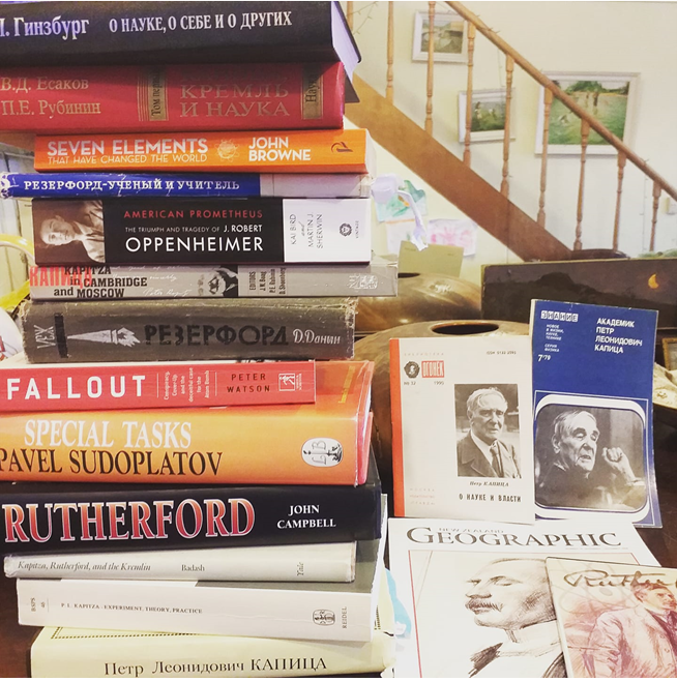

Figure 3. ‘Bombardment of Atoms and Decomposition of Nitrogen’ was published (Rutherford 1920)

In 1920, in the middle of the Russian Civil War, in Petrograd, when the Institutes could not be heated during the harsh Russian winters, staff were starving and the majority of students left, a Russian translation of Rutherford’s brochure ‘Bombardment of Atoms and Decomposition of Nitrogen’ was published (Rutherford 1920). Arguably, this was the first of Rutherford’s work published in Russia, and it came only two years after Rutherford’s discovery of the ‘transformation of elements’ or, in modern terminology, nuclear reactions. Rutherford’s name was transliterated into Russian as Rozeford. The Russian brochure contained four drawings and the annotation ‘This is a report in which the ‘modern alchemist’ sets out his discovery (the decomposition of nitrogen). The brochure assumes a trained reader’.

Figure 4. The Kapitza Memorial Museum in Moscow.

The recreation of an English park and Cambridge-style buildings in Moscow is eloquent testimony to the immense formative effect on Kapitsa of his time in Cambridge under his mentor and friend Rutherford.

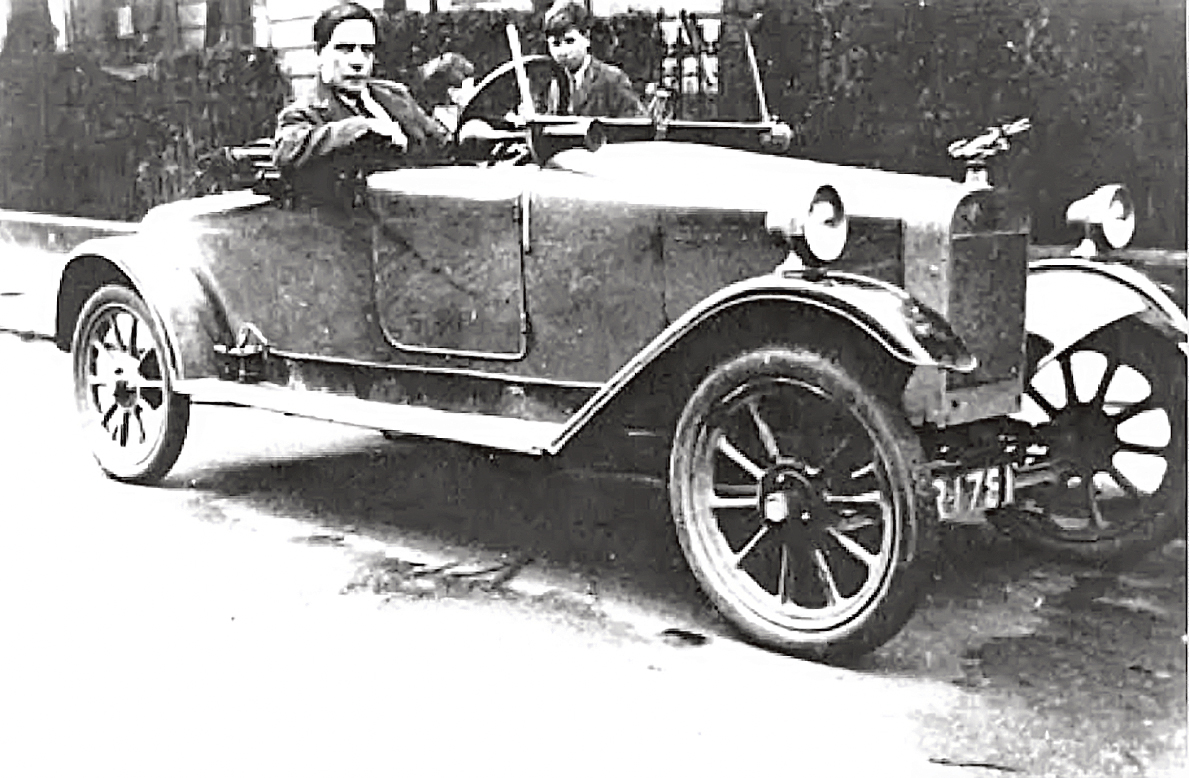

Figure 5. Pyotr Kapitsa in the automobile with the Crocodile mascot in the front, 1934. (From the Archives of the Kapitza Memorial Museum)

Kapitsa called Rutherford by the sobriquet ‘Crocodile’ which became a nickname for Lord Rutherford. One explanation is that Rutherford, intimidating for those in the laboratory, had heavy steps and they always could hear him approaching like the crocodile with the clock inside in ‘Peter Pan’. Later, in 1933 when Kapitsa was appointed the Director of the Mond laboratory, he asked that a key for the laboratory be made with a crocodile on it. He then commissioned the well-known English sculptor Eric Gill to carve both a plaque of Rutherford and a large Crocodile on the outer wall of the laboratory as a tribute to his mentor. The ‘crocodile’ became Kapitsa’s mascot through his whole life, his Memorial Museum in Moscow has all sorts of ‘crocodiles’.

Figure 6. Miniature platinum crucible, the only surviving item from the equipment sold by Rutherford to the Russians in 1914. (From the personal archive of Boris Stechkin, Shilov’s great-grandson)

Shilov’s plan was to use copy of Rutherford’s laboratory as the most prestigious and expensive laboratory for physical chemistry in Russia. Two years earlier Shilov had been able to buy from Marie Curie the equipment needed to set up a radiological laboratory at the Moscow Commercial Institute.

Sadly, the copies of Rutherford’s laboratory equipment intended for Moscow became an early casualty of the War to End All Wars. The ship carrying the equipment carefully selected by Rutherford was torpedoed and sunk.

The only item that survived the journey to Russia was an exact copy of the miniature platinum crucible that Rutherford used for highly pure chemical reactions. Shilov had carried it with him on his return journey in a wooden box-chest, which easily fitted into his bag. This crucible, as well as some letters, diaries and photographs taken by Shilov during his work with Rutherford and his stay in England, are today in the treasured possession of Nikolai Shilov’s great-grandson, Academician Boris Stechkin.

Figure 7. Desk medal “Rutherford. USSR Academy of Sciences to a Teacher of Science”, 1971 (From the Archives of the Kapitza Memorial Museum)

Rutherford’s Russian students keenly promoted their mentor by translating his works and by following Rutherford’s scientific ideas and his thoughts on intellectual freedom. They created stamps and medals in honour of this great New Zealander. The portraits of Rutherford can still be found on the walls of many Russian physics classrooms, alongside the portraits of Newton, Faraday and Mendeleev. Rutherford’s legacy was passed on by his Russian students to various of their students.

Figure 8. Rutherford and Kapitsa drinking tea from the Russian samovar at the Kapitza club, late 1920s – early 1930s. (From the Archives of the Kapitza Memorial Museum).

Kapitsa created his own ‘Kapitza Club’, a unique platform where junior on a par with senior scientists could present and discuss their research. It successfully functioned at the Cavendish many years after he left.

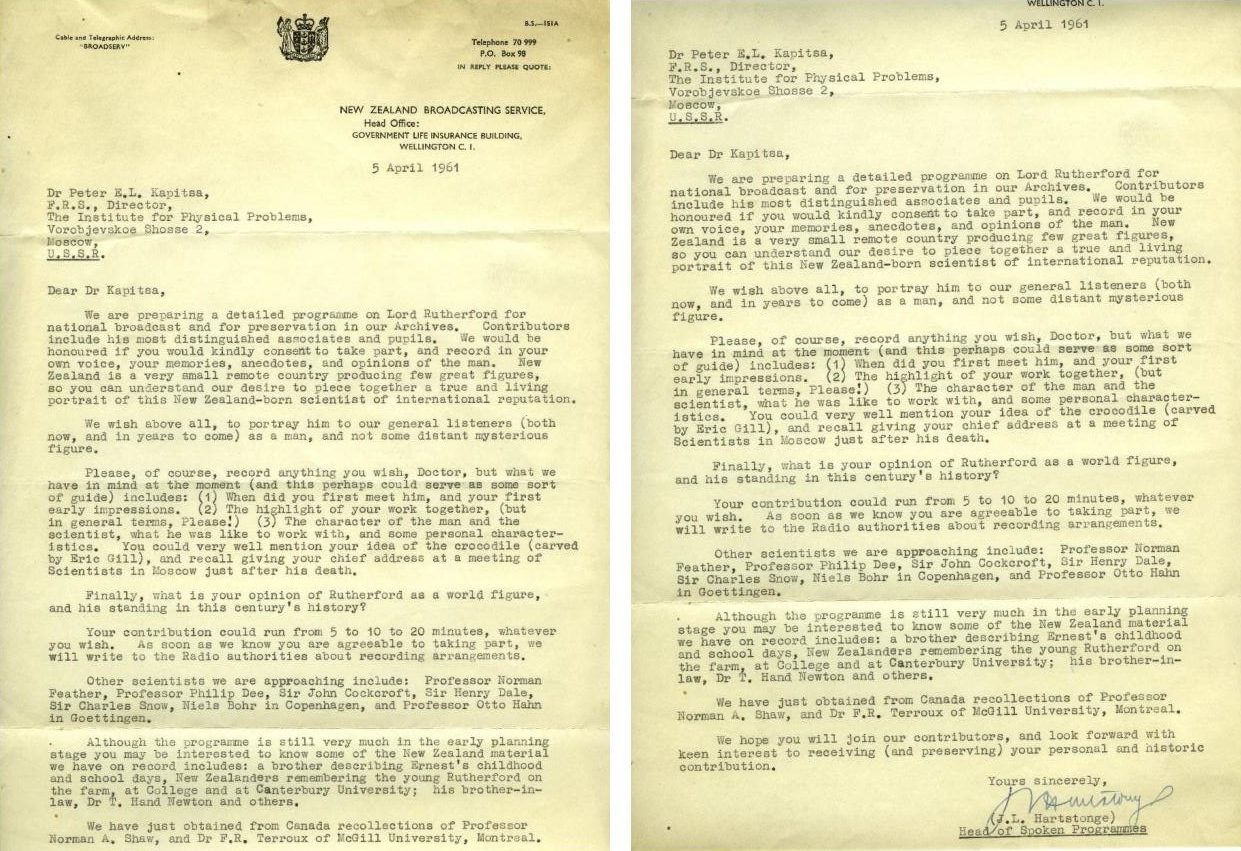

Figure 9. Letter about Rutherford and Russia from the New Zealand Broadcasting Service, 1961 (From the Archives of the Kapitza Memorial Museum)

While browsing through the primary sources back in Russia several years ago I came across a letter from the New Zealand Broadcasting Service (J.L.Hartstonge, Head of Spoken Programmes) dated 1961 and addressed to one of the Russian students of Rutherford – Pyotr Kapitsa. Hartstonge was asking Kapitsa to share with the New Zealand radio audience his memories of Rutherford.

Figure 10. Rutherfordium.

In the 1960s, small amounts of a new synthetic chemical element were produced in the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in the Soviet Union and at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. The priority of discovery and the naming were the subject of dispute for almost 40 years. In 1997 the teams involved resolved the dispute and adopted the current name rutherfordium. It remains a matter of conjecture: would the Russians have agreed to compromise had it been not in honour of Lord Rutherford who had contributed so much to Russian nuclear physics but to recognise a different foreign scientist without such Russian connection?

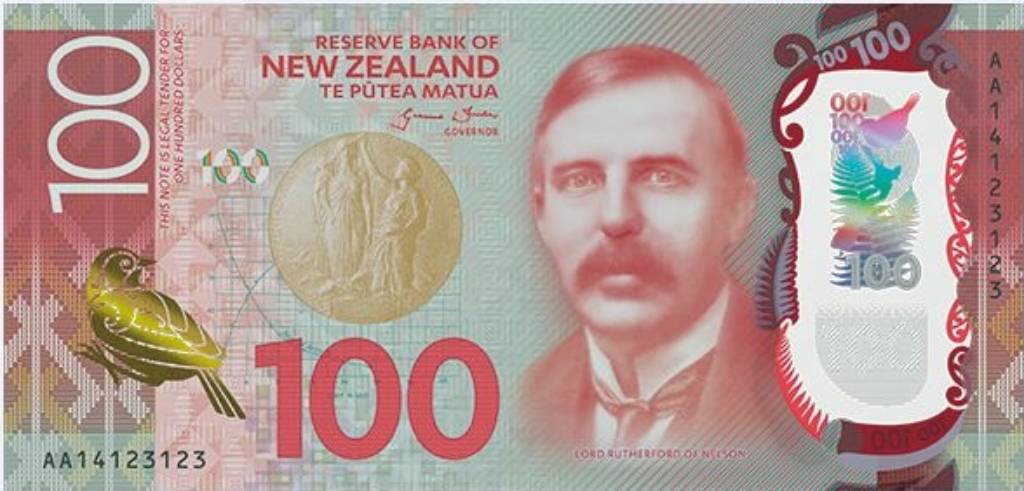

Figure 11. One-hundred-dollar denomination banknote, depicting Lord Rutherford of Nelson.

One of the most recognisable items is the highest value one-hundred-dollar denomination banknote, issued by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand depicting Lord Rutherford of Nelson.

Also depicted on the banknote is the Nobel Prize Medal in chemistry won by Rutherford in 1908 “for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances”. Overlaying the medallion is a graph plotting the results from Lord Rutherford’s investigations into naturally occurring radioactivity. The tukutuku panel used as a background on the $100 note is called Whaka-aro Kotahi from the Wharenui Kaa-kati at Whaka-tu Marae in Nelson close to Rutherford’s birthplace. (Rutherford identified strongly with the Nelson area and when he accepted his peerage he took the title Lord Rutherford of Nelson and sent a telegram to his mother: “Now Lord Rutherford. More your honour than mine. Ernest.” He chose as his coat of arms a design that included a kiwi and a Maori warrior).

On the reverse of the note is depicted a South Island lichen moth, it can be found in Fiordland beech forests. And a mohua or yellowhead, a small and colourful bird. It nests in tree holes, making it vulnerable to predators. It can be found in small isolated populations in the South Island and on islands off Stewart Island/Rakiura. Mohua is one of the endangered species and is a wonderful symbol of modesty, dignity and rare talent.

Figure 12. Special issue: The 150th anniversary of Rutherford’s birth, Rutherford and Russian Physics: the critical influence of the human factor, Olga Suvorova

My study published in April 2021 in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand contributes to the insufficiently investigated subject of the perception of Ernest Rutherford in Russia. It also examines Rutherford’s impact, both as a scientist and as an outstanding New Zealander, on matters of freedom of science in Imperial Russia and in the early Soviet Union and on human factors during times of social stress and repression. The examples given are drawn from a range of unique primary sources, in particular private correspondence between Rutherford and his Russian students and interns such as G. Antonoff, K. Yakovleff, J. Szmidt, N. Shilov, P. Kapitsa and others, their letters, diaries, photos and publications about their experience of working with Rutherford, including those available in the Russian language only, previously unpublished or unknown to academia.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03036758.2021.1914690